Questions 32-41 are based on the following

passage.

This passage is adapted from John Bohannon, “Why You Shouldn’t Trust Internet Comments.” ©2013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The “wisdom of crowds” has become a mantra of

the Internet age. Need to choose a new vacuum

cleaner? Check out the reviews on online merchant

Amazon. But a new study suggests that such online

5 scores don’t always reveal the best choice. A massive

controlled experiment of Web users finds that such

ratings are highly susceptible to irrational “herd

behavior”—and that the herd can be manipulated.

Sometimes the crowd really is wiser than you. The

10 classic examples are guessing the weight of a bull or

the number of gumballs in a jar. Your guess is

probably going to be far from the mark, whereas the

average of many people’s choices is remarkably close

to the true number.

15 But what happens when the goal is to judge

something less tangible, such as the quality or worth

of a product? According to one theory, the wisdom

of the crowd still holds—measuring the aggregate of

people’s opinions produces a stable, reliable

20 value. Skeptics, however, argue that people’s

opinions are easily swayed by those of others. So

nudging a crowd early on by presenting contrary

opinions—for example, exposing them to some very

good or very bad attitudes—will steer the crowd in a

25 different direction. To test which hypothesis is true,

you would need to manipulate huge numbers of

people, exposing them to false information and

determining how it affects their opinions.

A team led by Sinan Aral, a network scientist at

30 the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in

Cambridge, did exactly that. Aral has been secretly

working with a popular website that aggregates news

stories. The website allows users to make comments

about news stories and vote each other’s comments

35 up or down. The vote tallies are visible as a number

next to each comment, and the position of the

comments is chronological. (Stories on the site get an

average of about ten comments and about three votes

per comment.) It’s a follow-up to his experiment

40 using people’s ratings of movies to measure how

much individual people influence each other online

(answer: a lot). This time, he wanted to know how

much the crowd influences the individual, and

whether it can be controlled from outside.

45 For five months, every comment submitted by a

user randomly received an “up” vote (positive); a

“down” vote (negative); or as a control, no vote at all.

The team then observed how users rated those

comments. The users generated more than

50 100,000 comments that were viewed more than

10 million times and rated more than 300,000 times

by other users.

At least when it comes to comments on news

sites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise.

55 Comments that received fake positive votes from the

researchers were 32% more likely to receive more

positive votes compared with a control, the team

reports. And those comments were no more likely

than the control to be down-voted by the next viewer

60 to see them. By the end of the study, positively

manipulated comments got an overall boost of about

25%. However, the same did not hold true for

negative manipulation. The ratings of comments that

got a fake down vote were usually negated by an up

65 vote by the next user to see them.

“Our experiment does not reveal the psychology

behind people’s decisions,” Aral says, “but an

intuitive explanation is that people are more

skeptical of negative social influence. They’re more

70 willing to go along with positive opinions from other

people.”

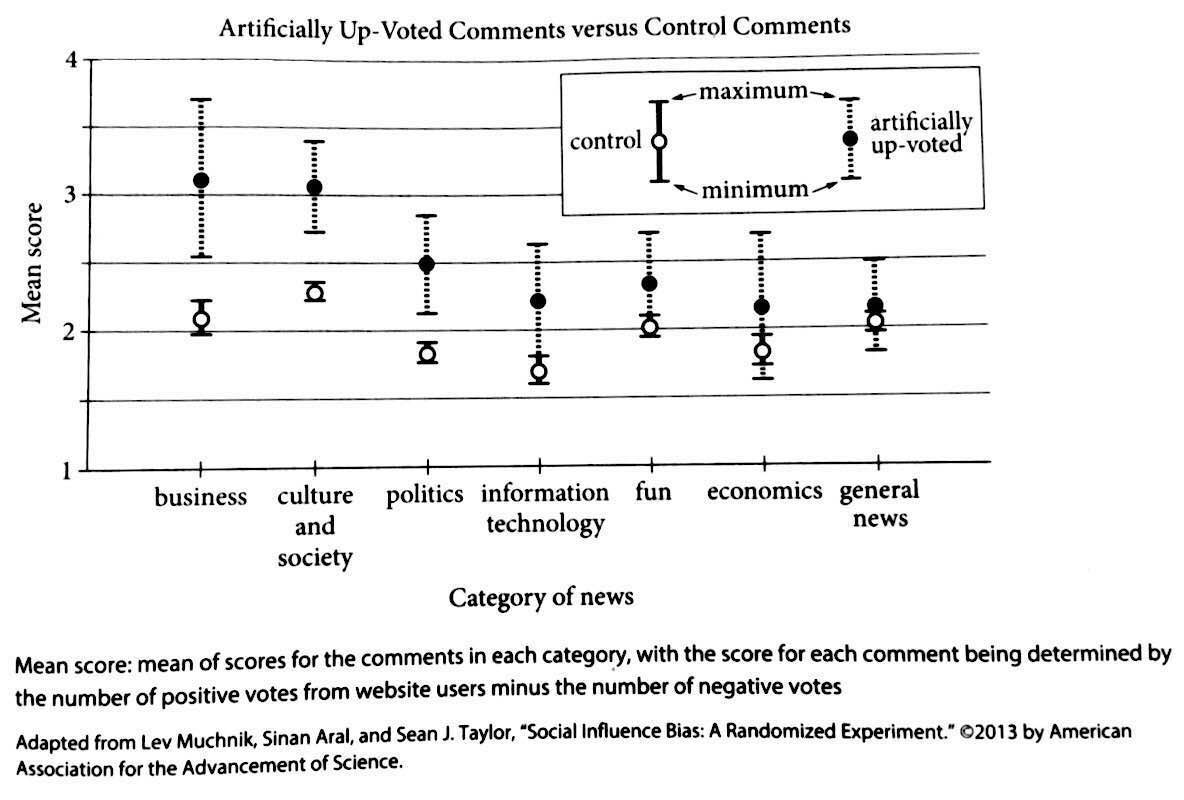

Duncan Watts, a network scientist at Microsoft

Research in New York City, agrees with that

conclusion. “[But] one question is whether the

75 positive [herding] bias is specific to this site” or true

in general, Watts says. He points out that the

category of the news items in the experiment had a

strong effect on how much people could be

manipulated. “I would have thought that ‘business’ is

80 pretty similar to ‘economics,’ yet they find a much

stronger effect (almost 50% stronger) for the former

than the latter. What explains this difference? If we’re

going to apply these findings in the real world, we’ll

need to know the answers.”

85 Will companies be able to boost their products by

manipulating online ratings on a massive scale?

“That is easier said than done,” Watts says. If people

detect—or learn—that comments on a website are

being manipulated, the herd may spook and leave

90 entirely.