Questions 11-21 are based on the following

passage.

This passage is adapted from Stephen Coleman, Scott Anthony, and David E. Morrison, “Public Trust in the News.” ©2009 by Stephen Coleman.

The news is a form of public knowledge.

Unlike personal or private knowledge (such as the

health of one’s friends and family; the conduct of a

private hobby; a secret liaison), public knowledge

5 increases in value as it is shared by more people. The

date of an election and the claims of rival candidates;

the causes and consequences of an environmental

disaster; a debate about how to frame a particular

law; the latest reports from a war zone—these are all

10 examples of public knowledge that people are

generally expected to know in order to be considered

informed citizens. Thus, in contrast to personal or

private knowledge, which is generally left to

individuals to pursue or ignore, public knowledge is

15 promoted even to those who might not think it

matters to them. In short, the circulation of public

knowledge, including the news, is generally regarded

as a public good which cannot be solely

demand-driven.

20 The production, circulation, and reception

of public knowledge is a complex process. It is

generally accepted that public knowledge should

be authoritative, but there is not always

common agreement about what the public needs to

25 know, who is best placed to relate and explain it, and

how authoritative reputations should be determined

and evaluated. Historically, newspapers such as The

Timesand broadcasters such as the BBC were widely

regarded as the trusted shapers of authoritative

30 agendas and conventional wisdom. They embodied

the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of

authority as the “power over, or title to influence, the

opinions of others.” As part of the general process of

the transformation of authority whereby there has

35 been a reluctance to uncritically accept traditional

sources of public knowledge, the demand has been

for all authority to make explicit the frames of value

which determine their decisions. Centres of news

production, as our focus groups show, have not been

40 exempt from this process. Not surprisingly perhaps

some news journalists feel uneasy about this

renegotiation of their authority:

Editors are increasingly casting a glance at the

“most read” lists on their own and other websites

45 to work out which stories matter to readers and

viewers. And now the audience—which used to

know its place—is being asked to act as a kind of

journalistic ombudsman, ruling on our

credibility (broadcast journalist, 2008).

50 The result of democratising access to TV news

could be political disengagement by the majority

and a dumbing down through a popularity

contest of stories (online news editor, 2007).

Despite the rhetorical bluster of these statements,

55 they amount to more than straightforward

professional defensiveness. In their reference to an

audience “which used to know its place” and

conflation between democratisation and “dumbing

down,” they are seeking to argue for a particular

60 mode of public knowledge: one which is shaped by

experts, immune from populist pressures; and

disseminated to attentive, but mainly passive

recipients. It is a view of citizenship that closes down

opportunities for popular involvement in the making

65 of public knowledge by reinforcing the professional

claims of experts. The journalists quoted above are

right to feel uneasy, for there is, at almost every

institutional level in contemporary society,

scepticism towards the epistemological authority of

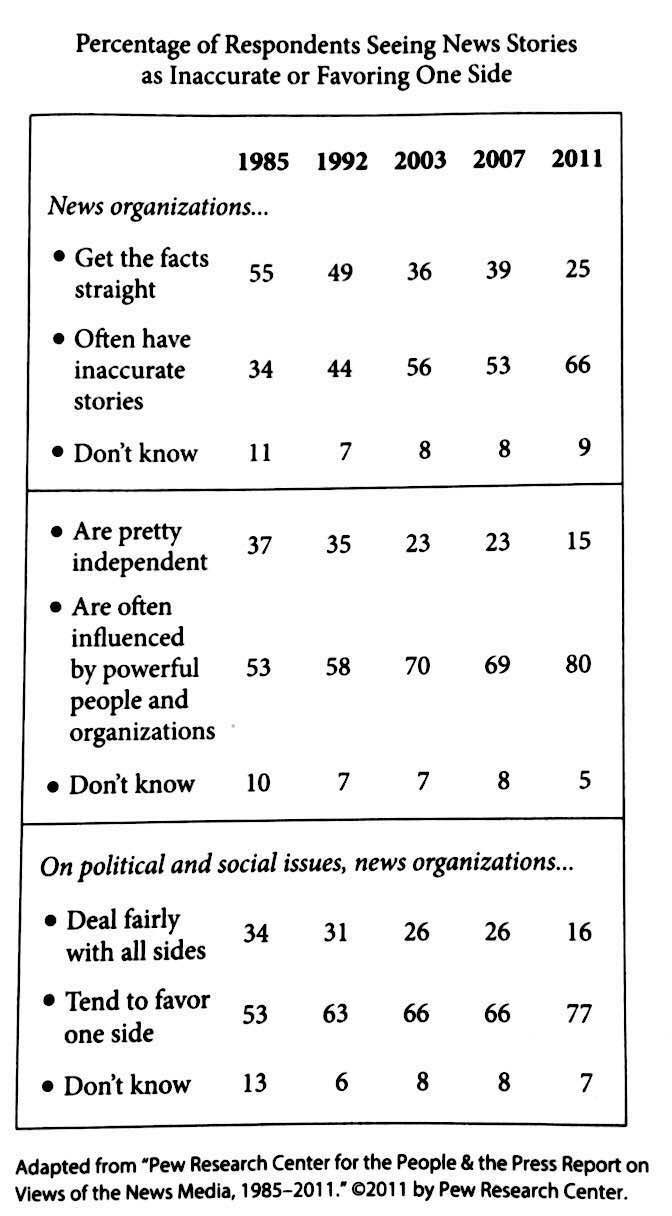

70 expert elites. There is a growing feeling, as expressed

by several of our focus group participants, that the

news media should be “informative rather than

authoritative”; the job of journalists should be to

“give the news as raw as it is, without putting their

75 slant on it”; and people should be given “sufficient

information” from which “we would be able to form

opinions of our own.”

At stake here are two distinct conceptions of

authority. The journalists we have quoted are

80 resistant to the democratisation of news:

the supremacy of the clickstream(according to

which editors raise or lower the profile of stories

according to the number of readers clicking on them

online); the parity of popular culture with “serious”

85 news; the demands of some audience members for

raw news rather than constructed narratives.